Wall painting

The first mention of the settlement dates back to 1318, but our first reliable date is very late, from 1422. The church does not appear on the registry of papal tithes either. In 1445 the son of László Bocz, voivode László acquired a new donation for the settlement.

This family claimed to be the descendent of voivode Boch of Belényes, who converted to the Catholic faith, and later the family members became Reformed. We have no medieval information about the church, and the post-Reformation archival material had also been moved after World War II, thus only on-site investigations can be used to get acquainted with its construction history. The church’s research was conducted by Tamás Emődi and József Lángi. The masonry church was built of large and irregular river stones in a single construction phase. Its layout is unusual, as its chancel is equal to the nave in width and it is semicircular in the interior, but angular in the exterior. The remains of its triumphal arch, its walled up sacristy door, tabernacles, and sedilia were found. Moreover, its converted, walled-up mediaeval windows have also surfaced. In 1882 it underwent a radical transformation, and thus its 1879 drawing by Ferenc Storno still depicted the mediaeval state.

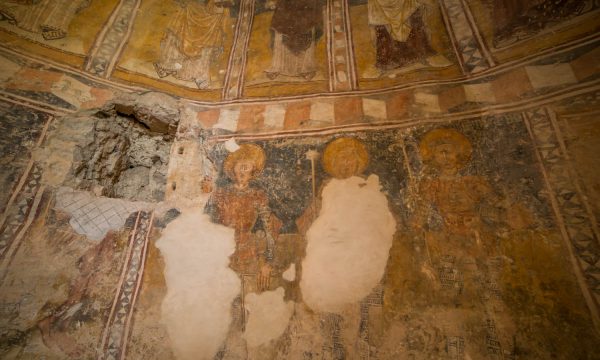

In 1927 its mural paintings were partially uncovered, but were whitewashed with the exception of two apostles and the holy kings. During our research, it turned out that except for the western wall the entire church was painted, and even the nave’s northern wall was decorated with figural representations. Two stylistically distinct mural cycles have surfaced. The sanctuary was decorated in its upper part by apostles and scenes from the Passion of Christ, below by Saint Bartholomew, the Hungarian holy kings, a female saint without attributes, and Saint Michael. On the northern wall of the nave we can see the work of the same master: in the upper register we can see Christ, a female saint without attributes, Saint Michael, in the middle the legend of Saint Ladislaus, Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus, and a holy bishop, while in the lower register the three Hungarian holy kings appear once again. On the southern wall, the same master represented the legend of Saint Margaret of Antioch.

The vaulting of the tower’s lowest level is dominated by a grand Maiestas Domini, on its northern and southern walls we see two evangelists each, holding the Holy Scriptures in their left hands, flanking seraphs. On the eastern wall, above the gate, the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus, on the western wall the fragments of two small saintly figures have survived, but as these were represented without attributes, they are unrecognisable. On the remaining surface a large number of 15th–17th century names and dates can be read. The earliest of these is the year 1474, thus the frescoes pertaining to the second period of painting were carried out prior to that date by a painter coming from an Orthodox cultural milieu. The fresco depicting the birth of Jesus and the fragment of a Mater Omnium representation on the northern wall are the work of this same master.

The legend of Saint Ladislaus was depicted in the middle register of the nave’s northern wall, beginning from under the gallery. Unfortunately, this cycle is much more deteriorated than the ones uncovered in the chancel, as when pulling down the rendering, the large hammer used caused serious damage to the weakened surface. We opened three larger probes, where parts of the battle scene were found under the gallery. Details of a decapitated head with braided beard and fragments of a body under the feet of trailing horses can be observed on the worn-out fresco. In the

central area we can identify the Cumans, who are depicted while shooting arrows backwards and wearing pointed hats with mail underneath. The Cuman’s beheading is the best preserved scene from this more than 8 m long cycle. The legend’s scenes are separated by tall stylised trees with straight trunks and rounded crowns. The painting of the three holy kings that has survived in the chancel is in a relatively good condition, despite the large missing parts. As in the case of Tileagd (Hu: Mezőtelegd), Saint Ladislaus stands on the left side, holding a short-handled battle axe in his right hand. The armours of the figures are identical here as well; they only wear breastplates, under which chainmail covers their entire body, while their shoulders and elbows are protected by rosette-like plates. Around their waist they carry wide belts on which swords hang, their hilts decorated with large pommels. The same weaponry is worn by the three fragmented figures uncovered on the northern wall, beneath the gallery. Since several repetitions can be observed on the murals, it cannot be ruled out that this too was a representation of the three Hungarian saint kings. Based on the outfits, the creation of the early layer can be dated to the late Angevine period or the early years of Sigismund’s reign.